DE

Mako und Clara Laila, Clara Laila und Mako. Immer zusammen, zu zweit mindestens, oft zu vielen, Wahlfamilie, Gefährt*innen. Manchmal vergesse ich, dass es eine Zeit gab in der sich die beiden nicht kannten, eine Zeit bevor sie Freundinnen* waren, in verschiedenen künstlerischen und aktivistischen Kreisen zusammengearbeitet haben, alle Schwere und Leichtigkeit geteilt haben.

Ich fange bei Mako an, weil ich Mako schon lange vor Clara Laila kannte. Oder zumindest war Mako immer irgendwie da, ganz am Anfang meiner Zeit an der Münchner Akademie. Dazu muss man sagen, dass diese Zeit der Münchner Akademie von alten weißen Alkoholiker-Choleriker-Professor-Männern geprägt war, die mich als Student*in auf dem Gang grundlos anschrien, die mit ihren Student*innen auf Weihnachtsparties knutschten, die Bewerber*innen im Aufnahmegespräch erniedrigten, die sowieso die ganze Zeit ihre ätzende Art des Provokativ-Seins als old school Karriere-Strategie raushingen ließen. Und von diesen Professor*innen gab es gleich einen ganzen Haufen. Wenn ich dahin zurück schaue, denke ich mir schon, wtf, was für ein normalisierter Irrsinn.

Das war also so das Umfeld, in dem wir uns befanden als Studierende. Und was für mich schon, als weiblich gelesene Person ätzend war, war für Mako als Person of Colour und dann auch noch als einzige* in der Kunstpädagogik-Klasse bzw. überhaupt eine* unter wenigen an der ganzen Akademie, gleich nochmal viel krasser. Konkret heißt das, zu allem Unistress, ständig rassistischen Kommentaren, Mikro-Aggressionen, Übergriffen ausgesetzt zu sein, sich ständig fehl am Platz fühlen, sich ständig erklären zu müssen und nicht verstanden werden. Dazu hatte Mako von Anfang an eine transmediale Praxis, also viele Themen und Formen gleichzeitig, Text, Vermittlungskonzepte, Recherche, Performance, Beton, Video. Aus einer antifaschistischen=antirassistischen Haltung heraus, und oft im Kollektiv. Eine Praxis, die sehr fern von der an der Münchner Akademie gängigen genialen Solo-Künstler*innenposition ist. Eine Praxis, die sich eben nicht als eine vereinzelte begreift, eine Praxis, die das Kunstprodukt als einen Teil der Arbeit versteht und nicht als das ultimative Ziel, auf das alles hinkulminiert.

Und dann kam Clara Laila aus Hamburg, wo sie Kunst, Erziehungswissenschaften und Geschichte studiert hatte, nach München in Makos Klasse. Clara Laila, die ähnliche Erfahrungen in Hamburger Institutionen gemacht hatte und die auf verwandte Weise wie Mako denkt und arbeitet, die sich auch für machtkritische Arbeit im öffentlichen Raum interessiert und dort auch immer wieder auf strukturelle Widerstände stößt. An der Münchner Akademie gab es zu der Zeit eine aktive Studierendenschaft. Mako und schnell auch Clara Laila waren wichtiger Teil davon, innerhalb der Kollektive PolizeiKlasse oder eRger (eure Recherche gegen rechts). Es war die Zeit, in der in München große, linke Demos stattfanden, wie die 2018 gegen das Polizeiaufgabengesetz zum Beispiel. Ich erinnere mich noch gut an das zarte Gefühl von Hoffnung; dass sich gemeinsam ja vielleicht doch was bewirken lässt, dass es nicht immer nur weiter abwärts gehen muss.

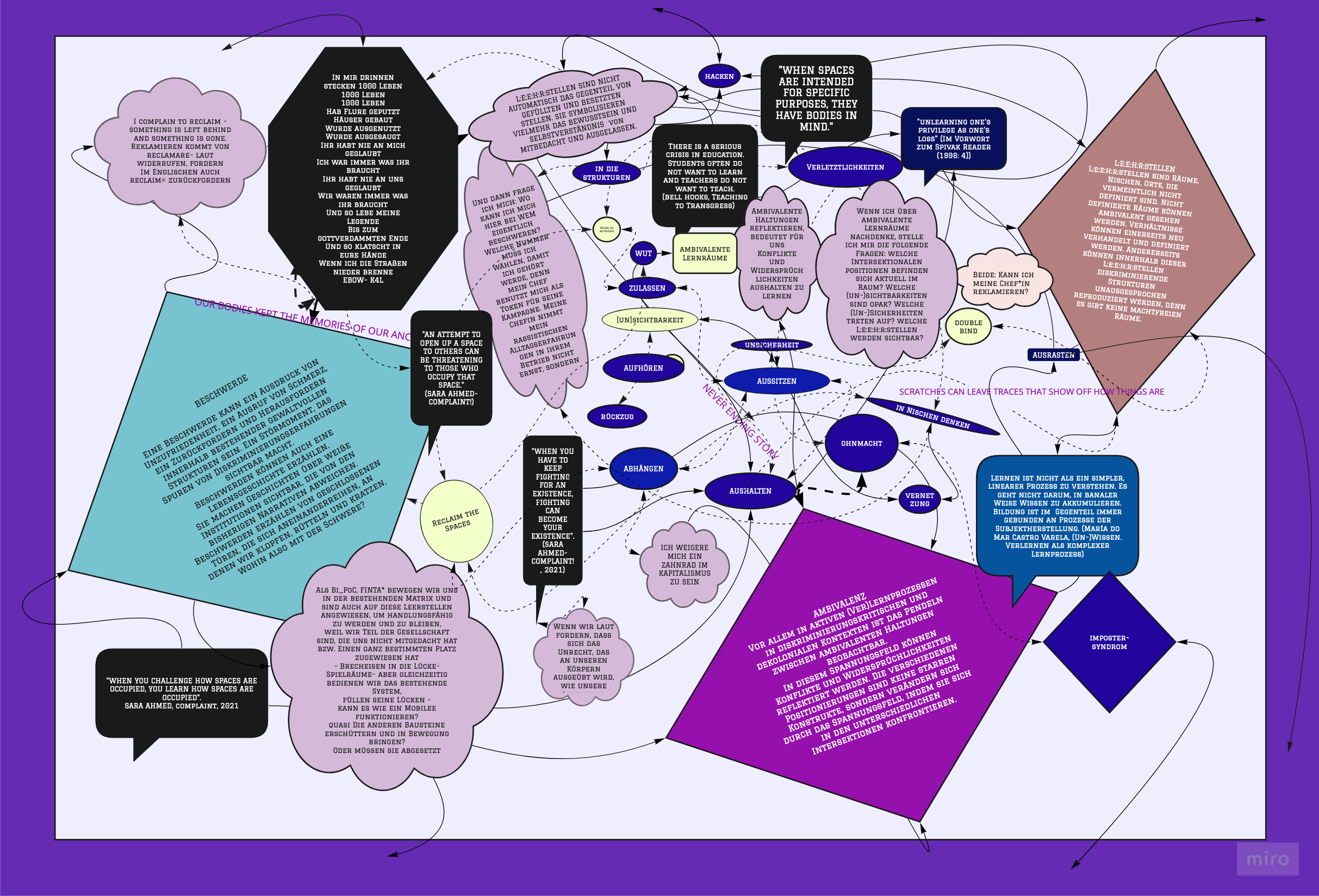

Ich habe mit Mako und Clara Laila in Vorbereitung zu diesem Text viel über die „Beschwerde“ gesprochen. Zuerst ganz einfach als Rechtsmittel, formell gerichtet an eine Institution. Aber ganz schnell schließen sich da Fragen an: an wen ist die Beschwerde zu richten? Was wenn es keine Beschwerdestelle gibt? Wenn es zum Beispiel keine eigenständige Anti-Diskriminierungsstelle gibt, die mit Vollzeitkräften besetzt ist, sondern nur eine Gleichstellungsstelle, die Mitglieder der Institution nur nebenbei zu ihren eigentlichen Aufgaben betreuen? Oder wenn es um Diskriminierungsformen geht, die als solche nicht erkannt oder ernst genommen werden? Und wer kann es sich überhaupt leisten, sich zu beschweren? Wer hat das Gefühl, sich beschweren zu können? Wer hat Erfolgsaussichten, für wen bedeutet es nur verschwendete Energie, die zu nichts führt und wer hat sogar Repressionen zu befürchten? Die beiden erzählen mir in dem Zusammenhang von Sarah Ahmeds Buch Complaint!. Ahmed beschäftigt sich darin mit mündlichen und schriftlichen Stellungnahmen von Studierenden und Mitarbeiter*innen an Universitäten, die sich über Ungleichbehandlung, Mobbing und Belästigung beschweren. In diesen Aussagen lässt sich einerseits ablesen, für wen die Institution gemacht ist, wen sie schützt, wer in Power ist, wie Beschwerden unterbunden werden und wer sich überhaupt beschweren kann. Sie leitet daraus eine feministische Pädagogik der Beschwerde ab: sich in Institutionen zu beschweren, bedeutet zu lernen, wie sie funktionieren und für wen sie arbeiten. Die Beschwerde als eine Art Markerflüssigkeit die die Struktur der Institution durchfließt und wie in einer Röntgenaufnahme von außen sichtbar werden lässt.

Die Schwere, die die Beschwerde begründet, bleibt. Sie geht tatsächlich in die Knochen. Die Schwere der Eltern etwa, die sich als körperliche Beschwerde auf die Kinder überträgt. Beschwerden, die ihren Ursprung haben in den Kämpfen der Eltern, deren Fluchterfahrungen, deren Ausbeutung und Unterdrückung und die an die Kinder und Kindeskinder vererbt werden. Wie sich also über Generationen Schwere aufbaut, die Communities of Struggle zusätzlich zu ihrer täglichen Erfahrung von Diskriminierung, von vornherein lähmt.

Du streifst mich

vielleicht denkst du

es sei harmlos

Du kratzt mich

Du kratzt mich

Du kratzt mich

Immer

und

immer wieder

Viele kleine Schnitte

an meinem Körper

Du kratzt mich

Zu viele Schnitte

dass mein Körper

mit dem Heilen nicht hinterherkommt1

Wohin also mit der Schwere? Um dieser Schwere begegnen zu können, braucht es Allianzen und Freund*innen. Um sich gegenseitig zu entlasten, kollektiv die Schwere zu tragen, eine solidarische Care-Praxis zu entwickeln. Mako und Clara Laila teilen die Schwere und sie teilen sie nicht nur innerhalb ihrer Freund*innenschaft sondern weit darüber hinaus. Und sie entwickeln ganz konkret künstlerische Räume und Ansätze um Veränderungen innerhalb von Institutionen zu bewirken, wie etwa gemeinsam mit Raphael Daibert als Third Space: Disordering the Mess2. Sie agieren als Vermittler*innen zwischen weißen (Kunst-)Institutionen und Communities of Struggle. Nicht, damit sich die weißen Institutionen dann mit der eigenen „Diversität“ schmücken können, sondern um die immergleichen Muster der Verletzung durch strukturelle Gewalt und Rassismus zu durchbrechen. Damit die institutionellen Ressourcen, Möglichkeiten und Räume für eine unsichtbar gemachte Öffentlichkeit überhaupt erst zugänglich und brauchbar werden.

Ich bewundere Makos und Clara Lailas Arbeit schon lange, die scheinbar endlos großzügig ist, gegenüber allen Menschen. Die in ihrer Haltung radikal links ist, in ihrer Praxis nie dogmatisch, immer im Hoffen auf eine Verbesserung, auf die Möglichkeit der Vermittlung zwischen den Menschen, und zwischen den Menschen und den Institutionen. Ich denke, ich habe in den letzten Jahren von kaum jemanden so viel ge- und verlernt wie von diesen beiden. Für Ruine habe ich Clara Laila und Mako als Künstler*innen eingeladen, denen diese Einladung im besten Fall Freude bereitet und den beiden Zeit für sich einräumt, die sonst selten vorhanden ist.

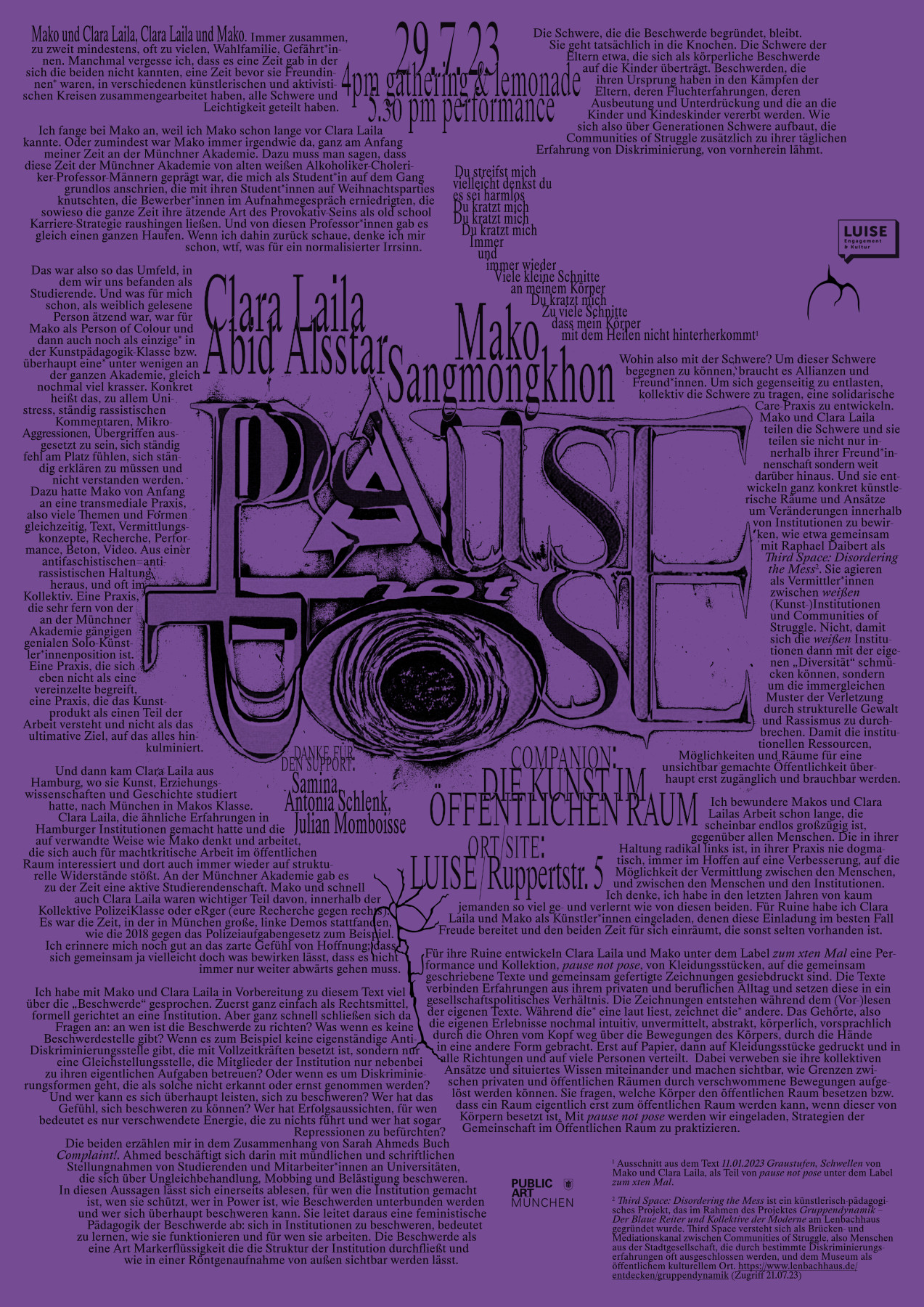

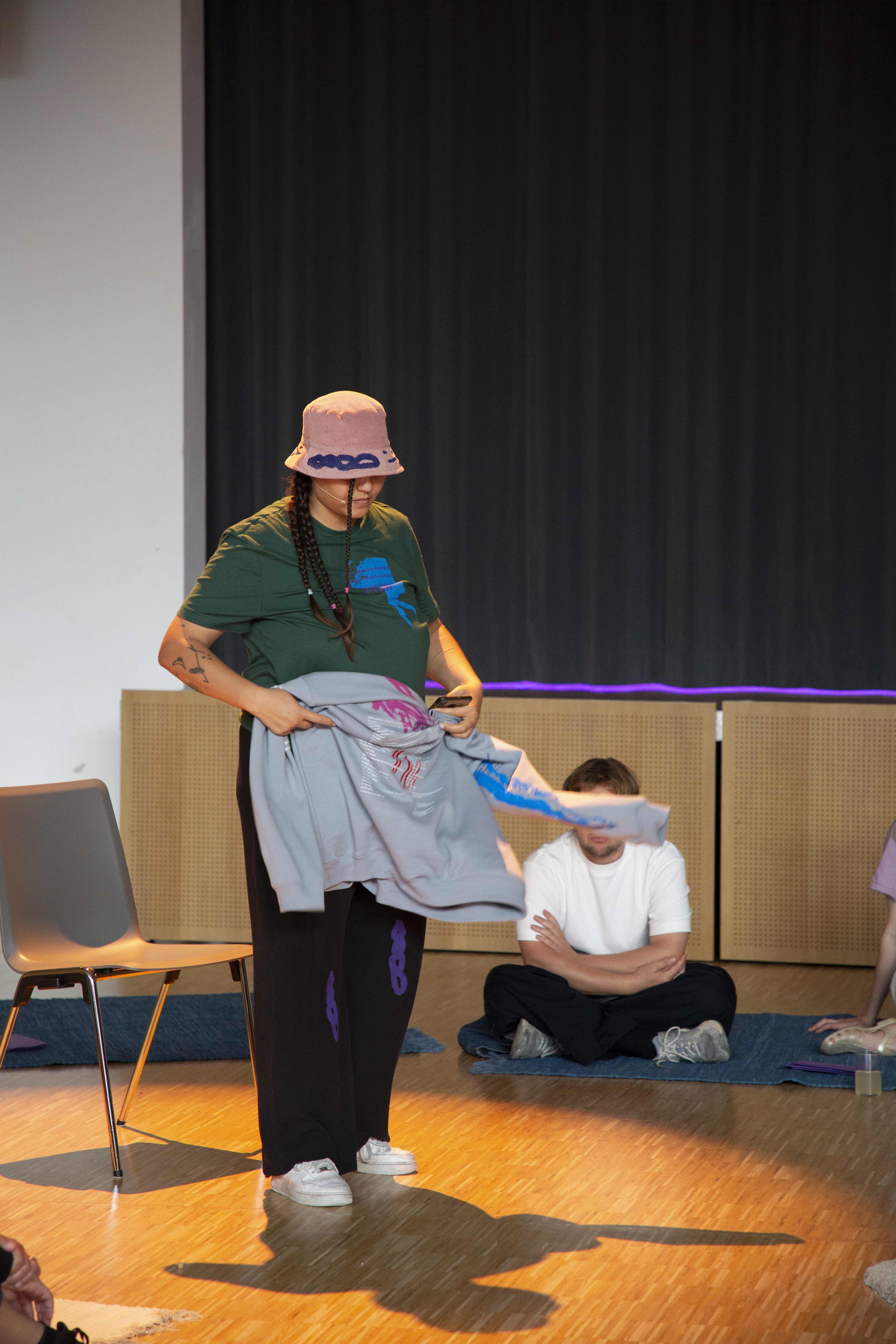

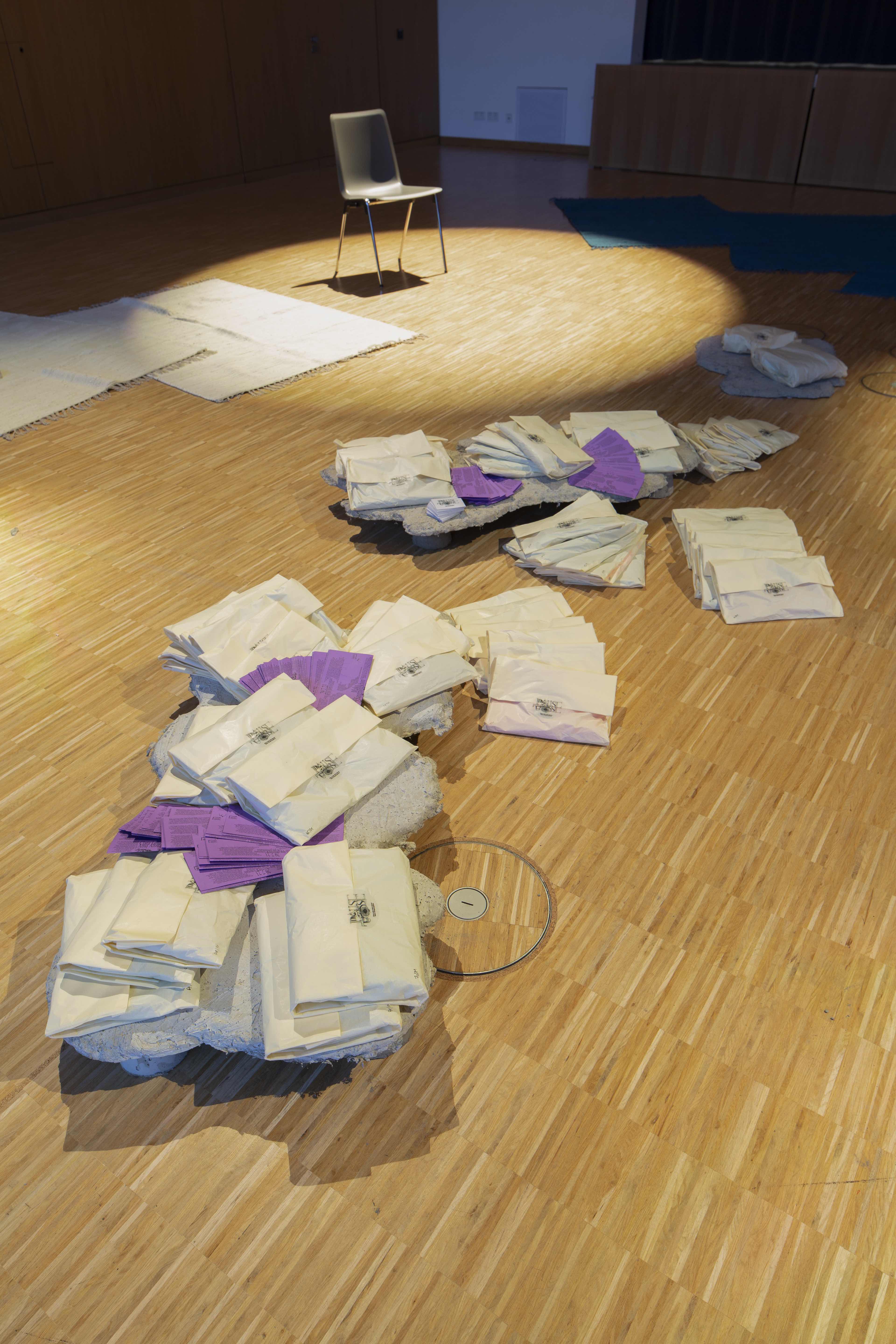

Für ihre Ruine entwickeln Clara Laila und Mako unter dem Label zum xten Mal eine Performance und Kollektion, pause not pose, von Kleidungsstücken, auf die gemeinsam geschriebene Texte und gemeinsam gefertigte Zeichnungen gesiebdruckt sind. Die Texte verbinden Erfahrungen aus ihrem privaten und beruflichen Alltag und setzen diese in ein gesellschaftspolitisches Verhältnis. Die Zeichnungen entstehen während dem (Vor-)lesen der eigenen Texte. Während die* eine laut liest, zeichnet die* andere. Das Gehörte, also die eigenen Erlebnisse nochmal intuitiv, unvermittelt, abstrakt, körperlich, vorsprachlich durch die Ohren vom Kopf weg über die Bewegungen des Körpers, durch die Hände in eine andere Form gebracht. Erst auf Papier, dann auf Kleidungsstücke gedruckt und in alle Richtungen und auf viele Personen verteilt. Dabei verweben sie ihre kollektiven Ansätze und situiertes Wissen miteinander und machen sichtbar, wie Grenzen zwischen privaten und öffentlichen Räumen durch verschwommene Bewegungen aufgelöst werden können. Sie fragen, welche Körper den öffentlichen Raum besetzen bzw. dass ein Raum eigentlich erst zum öffentlichen Raum werden kann, wenn dieser von Körpern besetzt ist. Mit pause not pose werden wir eingeladen, Strategien der Gemeinschaft im Öffentlichen Raum zu praktizieren.

(Ruine München, Juli 2023)

1 Ausschnitt aus dem Text 11.01.2023 Graustufen, Schwellen von Mako und Clara Laila, als Teil von pause not pose unter dem Label zum xten Mal.

2 Third Space: Disordering the Mess ist ein künstlerisch-pädagogisches Projekt, das im Rahmen des Projektes Gruppendynamik – Der Blaue Reiter und Kollektive der Moderne am Lenbachhaus gegründet wurde. Third Space versteht sich als Brücken- und Mediationskanal zwischen Communities of Struggle, also Menschen aus der Stadtgesellschaft, die durch bestimmte Diskriminierungserfahrungen oft ausgeschlossen werden, und dem Museum als öffentlichem kulturellem Ort. https://www.lenbachhaus.de/entdecken/

gruppendynamik (Zugriff 21.07.23)

Clara Laila Abid Alsstar versteht sich

als Konzeptkünstlerin, Kunstvermittlerin, researcher, und performt in spoken

words. Zusätzlich organisiert sie sich in kollektiven Zusammenschlüssen. Geboren

und aufgewachsen in Hamburg, ist sie Teil des Kollektivs Third Space:

Disordering the Mess, und eRger und leitet den städtischen Kunstraum

FLORIDA Lothringer 13 in München. Schwerpunkt ihrer künstlerischen,

kuratorischen und kunstvermittlerischen Praxis ist das Verarbeiten von

situiertem Wissen zu Diskriminierungserfahrungen, social justice und die

kritische Befragung von bestehenden Machtstrukturen in soziokulturellen und

-politischen Kontexten.

Mako Sangmongkhon versteht sich als

Künstler*in, Aktivist*in und Kunstvermittler*in. M bewegt sich an den

Schnittstellen der Selbstorganisation, meta-ästhetischem Aktivismus,

rassismuskritischer und antifaschistischer Kultur- und Bildungsarbeit, verstreut

und versammelt sich am liebsten in Gruppen wie dem Third Space: Disordering

the Mess oder eRger (eure Recherche gegen rechts) oder checkt die

Lage mit Komplizin Clara Laila Abid Alsstar ab. Dabei ist es M wichtig,

intersektionale Politiken, Perspektiven und deren verbundene Wut künstlerisch in

den öffentlichen Raum zu rücken, gegen autoritäre Herrschaftsstrukturen, sowie

institutionellem Rassismus entgegenzutreten. Neben dem künstlerischen Schaffen,

der Care-Work als Elternteil und auch als Freund*in, promoviert M an der

Kunsthochschule Mainz.

EN

Mako and Clara Laila, Clara Laila and Mako. Always together, the two at least, and sometimes many more, chosen family, companions. Sometimes I forget that there was a time when they didn’t know each other, a time before they were friends, working together in different artistic and activist circles, sharing all burdens and joys.

I’ll start with Mako because I knew Mako long before I knew Clara Laila. Or at least Mako was always there somehow, at the very beginning of my time at the Munich Academy. It should be said that this time at the Munich Academy was characterised by old white alcoholic choleric male professors who yelled at me as a student in the hallway for no reason, who made out with their students at Christmas parties, who humiliated applicants in the admissions interview, who, in whatever way, constantly wore their toxic provocative behaviour on their sleeves as an old school, career strategy. And there were a whole bunch of these professors. When I look back, I think to myself, wtf, what a normalised insanity.

That was the environment we found ourselves in as students. And that sucked for me as a person who was seen as female, sucked even more for Mako as a person of colour, as the only one in their art pedagogy class or one among a few at the whole academy. To sum it up, this means, on top of all the university stress, being constantly exposed to racist comments, micro-aggressions, assault, constantly feeling out of place, constantly having to explain oneself, and not being understood. To this end, Mako had a transdisciplinary practice from the beginning, meaning many themes and mediums at the same time: text, concepts of mediation, research, performance, concrete, video. From an antifascist = antiracist position and often in a collective. A practice that is very far from the individual genious artist position common at the Munich Academy. A practice that does not see itself as an isolated one, a practice that understands the art product as a part of the work and not as the ultimate goal to work towards.

And then Clara Laila from Hamburg, where she studied art, education and history, came to Munich to join Mako’s class. Clara Laila, who had similar experiences at Hamburg institutions and who thinks and works in a similar way to Mako. Who is also interested in power-critical work in public space, and who also constantly encounters structural resistance. During their time, there was an active student body at the Munich academy. Mako, followed by Clara Laila, were an important part of it, being both in the collectives PolizeiKlasse1 and eRger (eure Recherche gegen rechts)2. It was the time when big, left-wing demos took place in Munich, like the 2018 demo against the new Law on Police Duties. I still remember the tender feeling of hope, that, collectively, maybe something can be achieved, that things don’t always have to get worse.

I talked a lot with Mako and Clara Laila about the ‘complaint’ in preparation for this text. At first, quite simply as a legal action, formally addressed to an institution. But very quickly questions arose; who should the complaint be addressed to? What if there is no body of complaint? What if, for example, there is no independent, anti-discrimination office staffed with full-time employees, but only an equal opportunities office that members of the institution only supervise as a side job to their actual duties? Or when it comes to forms of discrimination that are not recognised as such or taken seriously? And who, first of all, can afford to complain? Who has the ability to complain? Who has a chance of success, who will it mean wasted energy for and lead to nothing, and who should fear repression? The two of them tell me about Sarah Ahmed’s book Complaint!, Ahmed deals with oral and written statements of students and employees at universities who complain about unequal treatment, bullying and harassment. These statements reveal, on the one hand, who the institution is made for, who it protects, who is in power, how complaints are stopped, and who is able to complain. From this she produces a feminist pedagogy of the complaint: to complain in institutions is to learn how they work and who they work for. The complaint as a kind of marker fluid that flows through the structure of the institution, making it visible to the outside, like an x-ray.

The effect or burden or trauma3 that caused the complaint remains with us. It actually goes to the bones. An example is the trauma of parents, passed on to their children, expressing itself through or within the body. The trauma that originated in the parents’ struggles; their migration experiences and their experiences of exploitation and oppression, are inherited by their children, and their children’s children. These effects build up over generations, burdening Communities of Struggle and adding to their daily experiences of discrimination.

You touch me

maybe you think

it is harmless

You scratch me

You scratch me

You scratch me

Always

and

again and again

Many little cuts

on my body

You scratch me

Too many cuts

my body

can’t keep up with the healing4

So where to go with trauma? Allies and friends are needed to confront trauma. To relieve each other, to collectively carry trauma, to develop a practice of care in solidarity. Mako and Clara Laila share trauma, not only in their friendship but far beyond it. Together they develop very concrete artistic spaces and approaches to bring about change within institutions. One such example is with Raphael Daibert in Third Space: Disordering the Mess5. Through Third Space they act as mediators between white (art) institutions and Communities of Struggle. This isn’t done so white institutions may claim a label of ‘diversity’, but in order to break the same patterns of violation produced by structural violence and racism. They do this so that institutional resources, opportunities and spaces are accessible and available to a public made invisible.

I have long admired Mako and Clara Laila’s work, which is endlessly generous to everyone. Radically leftist in its attitude, never dogmatic in its practice, always hoping for an improvement, for the possibility of mediation between people, and between people and institutions. I don’t think I have learnt and unlearnt as much from anyone as from these two in recent years. For Ruine, I invited Clara Laila and Mako as artists, who, at best, will enjoy the invitation as it allows them time for themselves, something rarely available.

For their Ruine Clara Laila and Mako have developed, under the label zum xten Mal, a performance and collection titled pause not pose, made up of garments they have screen printed their collective texts and drawings on. The texts are a combination of experiences take from their private and professional lives, dissolving them into a socio-political relationship. The drawings are made while reading their own texts. While one reads aloud, the other draws. What is listened to, their own experiences, are then again intuitively, directly, abstractly, physically, pre-linguistically, through the ears and away from the brain, and through the movements of the body and hands, brought into a new form. First put down on paper, then printed on pieces of clothing and distributed among many people in all directions. By doing this they interweave their collective approaches and situated knowledge, making visible the dissolving of boundaries between private and public spaces through abstract movements. They ask which bodies occupy public space and suggest spaces are only able to become public when occupied by bodies. pause not pose invites us to practice strategies of community in public space.

(Ruine München, July 2023)

1 PolizeiKlasse translates to ‘Police Class Collective’

2 ‘eure Recherche gegen rechts’ translates to ‘your research against the right’

3 The word ‘Schwere’ originally used in the German text refers to the word ‘Beschwerde’ which translates to ‘complaint’. Both words have a connection to the idea of a negative weight, load or burden being put upon someone or something. Examples of this can range from financial, work or familial burdens to more direct, physiological/ bodily impact, stress or trauma.

4 Excerpt from the text 11.01.2023 Graustufen, sleepers by Mako and Clara Laila, as part of pause not pose under the label zum xten Mal.

5 Third Space: Disordering the Mess is an artistic-pedagogical project founded as part of the project Gruppendynamik — Der Blaue Reiter und Kollektive der Moderne at the Lenbachhaus. Third Space sees itself as a bridge and mediation channel between Communities of Struggle, i.e. people from urban society who are often excluded from certain experiences via discrimination, and the museum as a public cultural space. https://www.lenbachhaus.de/entdecken/gruppendynamik (accessed 21.07.23)

Clara Laila Abid Alsstar sees herself as a conceptual

artist, art mediator and researcher who performs using spoken word. In addition

to these roles, she is involved in various collective projects. Born and raised

in Hamburg, she is part of the collective Third Space: Disordering the Mess,

eRger, and co-runs the art space, FLORIDA Lothringer 13, in Munich. The focus of

her artistic, curatorial, and art mediatory practices is the processing of

situated knowledge on experiences of discrimination, social justice, and the

critical questioning of existing power structures in socio-cultural and

political contexts.

Mako Sangmongkhon sees themselves as an

artist, activist and art mediator. Mako moves between the intersections of

self-organisation, meta-aesthetic activism, racism-critique and anti-fascist

cultural and educational work, scattering and gathering in groups such as Third

Space: Disordering the Mess, eRger (eure Recherche gegen rechts) or checking out

various projects with accomplice Clara Laila Abid Alsstar. In doing so, it is

important to Mako to artistically move intersectional politics and perspectives,

and their associated rage, into the public space, and to oppose authoritarian

structures of domination and institutional racism. In addition to their artistic

work, Mako participates in care work as a parent and as a friend. Mako is

currently completing a PhD at the Kunsthochschule Mainz.